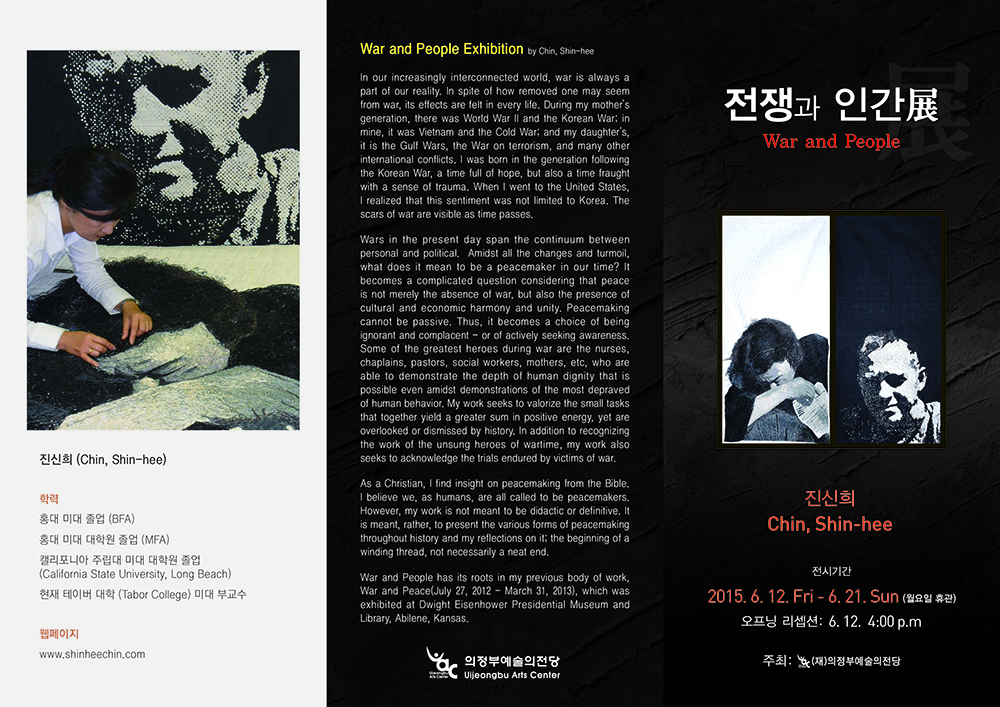

전쟁과 인간

강신희

이번 전시회는 전쟁과 억압의 상흔 속에 피어나는, 평화에 대한 희망과 생명에의 경외를 이야기하려는 의도로 기획됐다. 대부분의 작품은 분쟁과 폭력으로 인해 삶이 뒤틀어진 개인과 군상의 얼굴을 형상화한 것이다. 이 작품을 통해, 비극으로 인한 상실의 아픔, 인간 생명의 소중함, 극한 절망과 공포에도 굴하지 않는 평범한 이들의 희망과 용기, 그리고 자유와 정의에 대한 갈망이라는 인간의 보편적인 경험과 이상을 드러내 보이고자 하였다.

이 전시회에는 일제의 식민지 지배, 2차대전, 한국전 등 지구촌 분쟁과 관련된 인물의 초상이 주를 이루고 있다. 특히 전시회가 한국전 초기의 주요 전장이었던 의정부에서, 한국전 (6.25전쟁) 발발 65 주년 기념기간 중 열린다는 점을 고려해 작품을 선정했다. 한국전에서 전사하거나 실종된 미군 병사, 미군 아들의 전사 통보서를 받아 든 어머니, 전쟁 고아의 미국 입양을 시작한 평범한 여인, 분단으로 인해 이산의 아픔 속에 살아가는 나의 가족의 모습 등 모두 28점이다.

아울러 최근 논란이 되고 있는 일본 침략 역사 왜곡과 관련해 “위안부”, “안중근 의사”, “두 왕국 이야기” 등의 작품도 포함됐다. 또한 전쟁과 뿌리를 같이하는 억압, 식민화라는 비인간적 지배, 여성에 대한 편견, 특정 인종에 대한 차별과 학살에 맞서 분연히 일어선 무명 영웅의 얼굴도 담아 보았다.

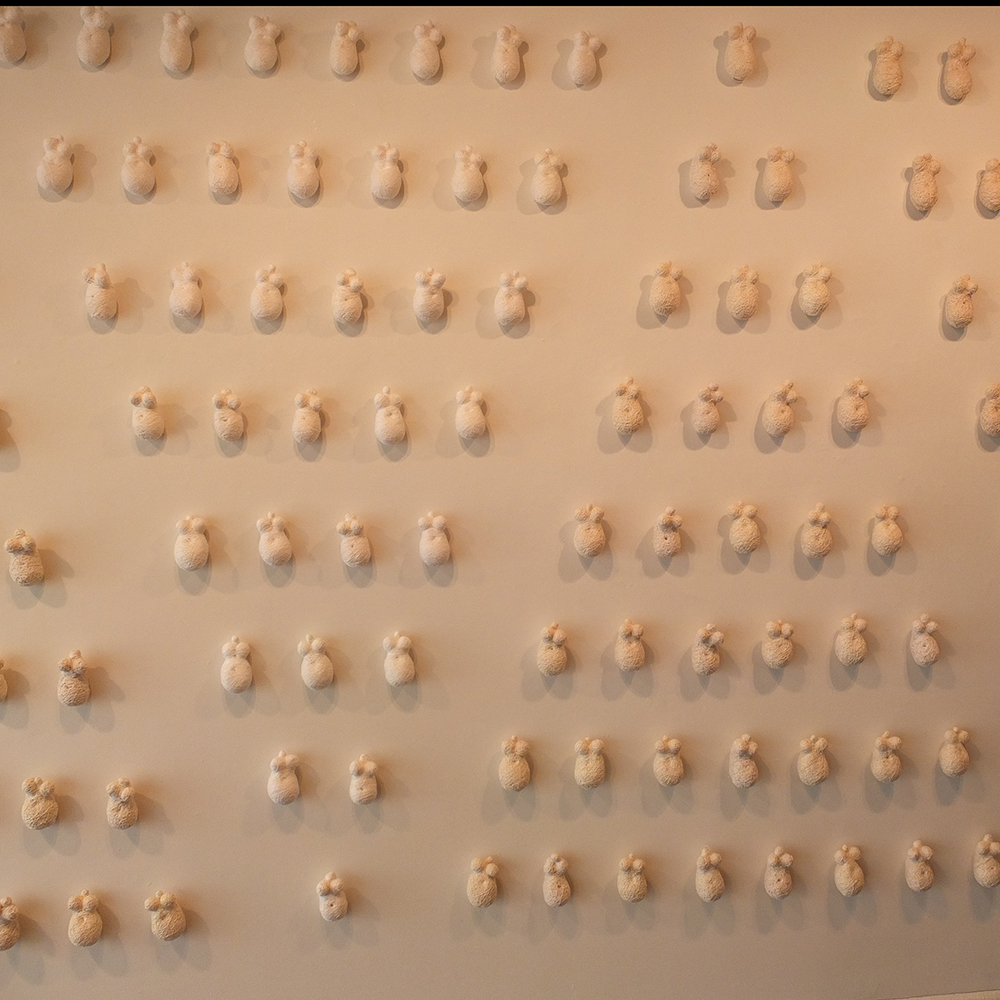

모든 작품은 섬유 작품이다. 천 위에 실을 무작위적으로 뿌린 뒤 바느질 (random stitching) 하거나, 한국의 전통종이공예인 지승을 헝겊에 적용한 작품, 천으로 만든 요요 (yo-yo)를 이용해 퀼트로 제작하는 기법이 사용됐다.

이번 전시회는 미국 아이젠하워 대통령 박물관 (Dwight Eisenhower Presidential Museum and Library)에서 열렸던 진신희 작가의 개인전 -“전쟁과 평화” (War and Peace, 7월 15, 2012 -3월 31일, 2013)-을 모태로 하고있다.