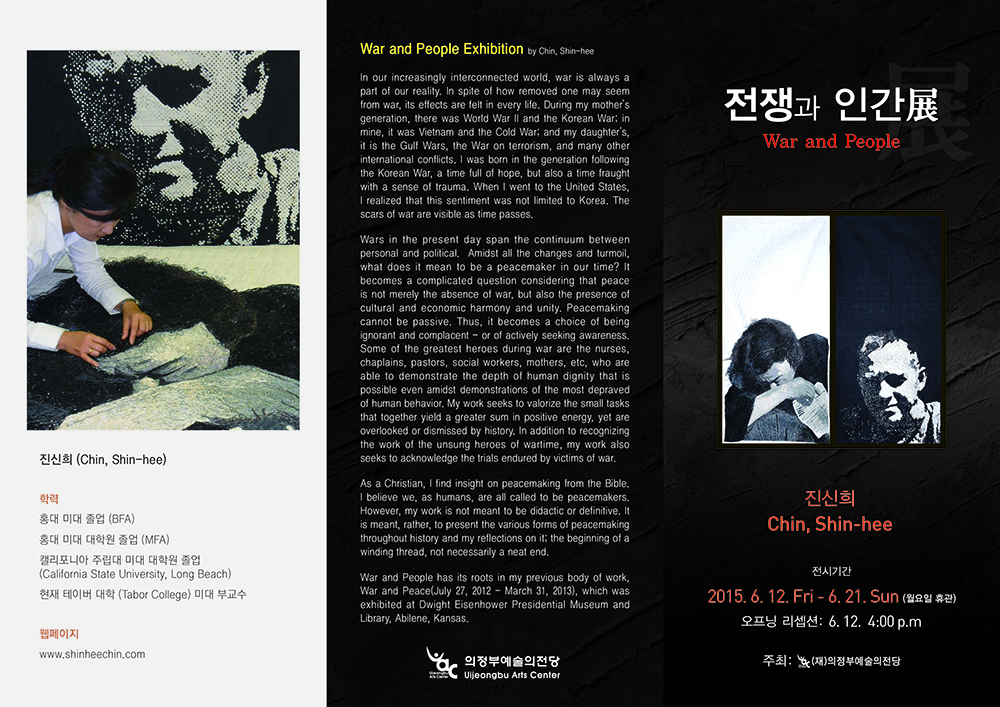

Because my worldview has been shaped by my experiences as a woman, a mother, and an immigrant, my work is an effort to draw connections between my inner life and the world beyond.

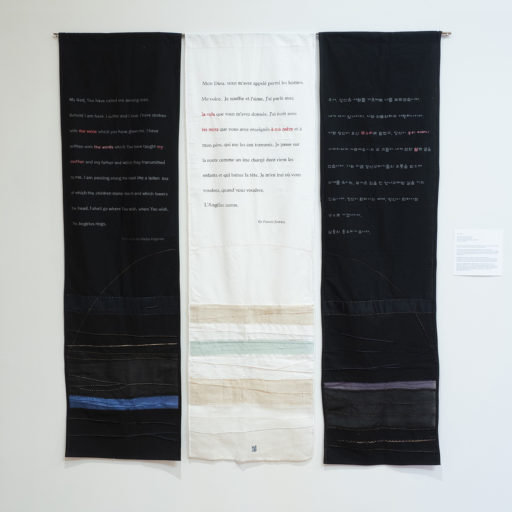

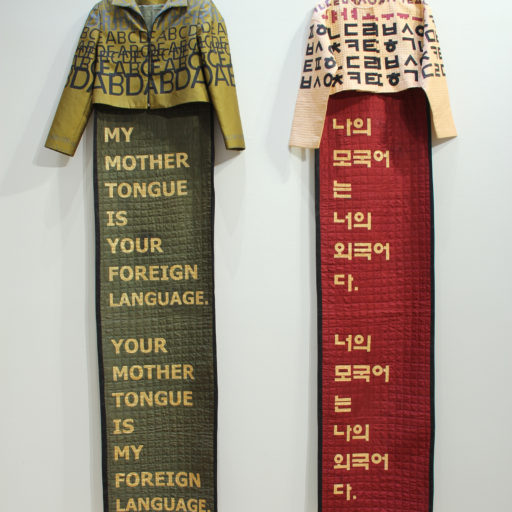

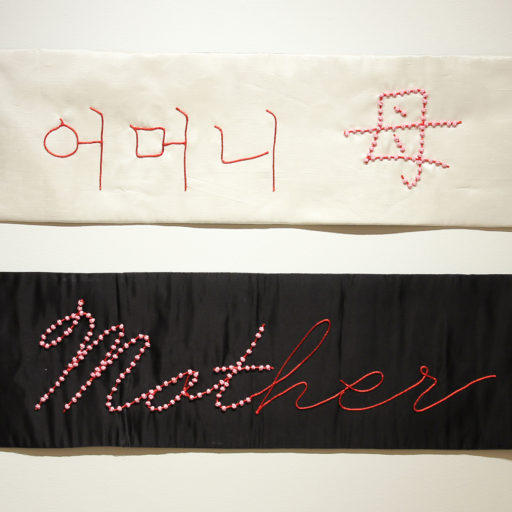

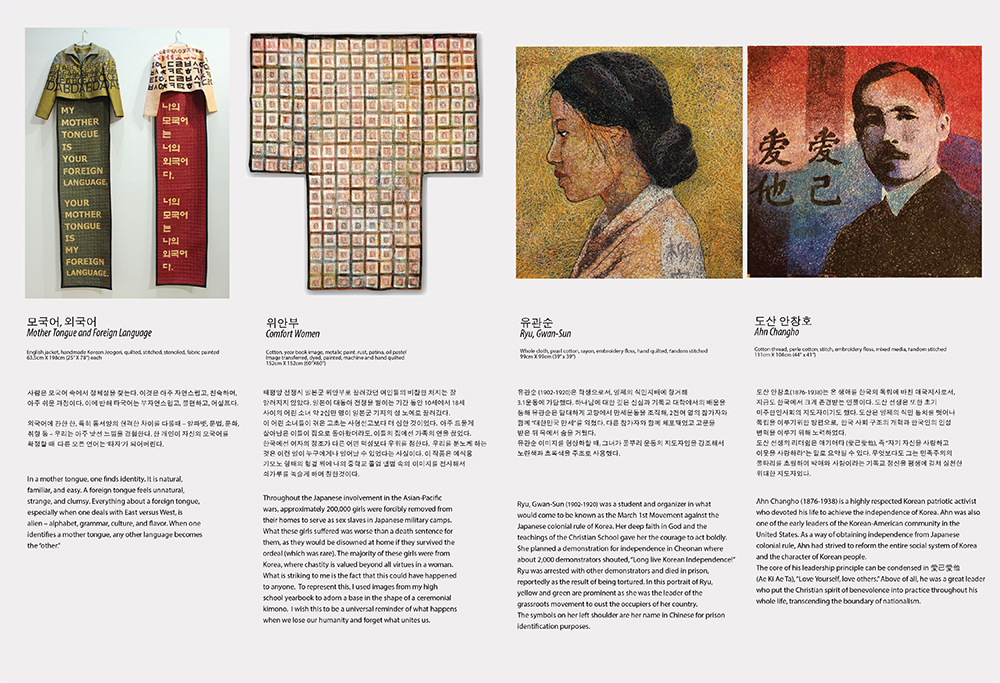

I spent the first 29 years of my life in Korea, speaking Korean, living amongst Korean people. When I immigrated to America, I found that in order to communicate I had to abandon my mother tongue. In this way, I had to re-orient my identity; my relationship to the world. Abandoning my mother tongue did not mean instant assimilation; to this day, I am an “other” because of my accent, my understanding of grammar is different. There was a distinct sense of loss, of losing my cultural identity.

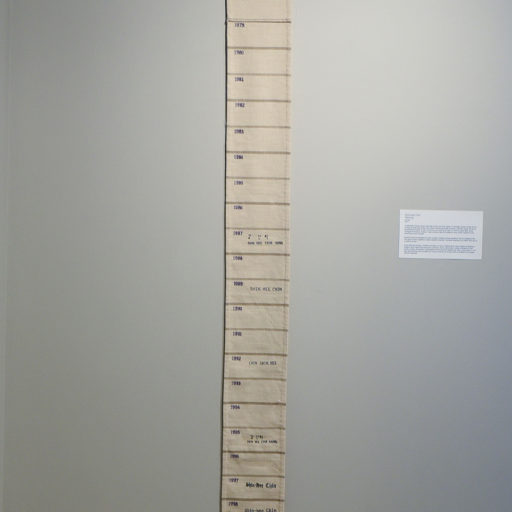

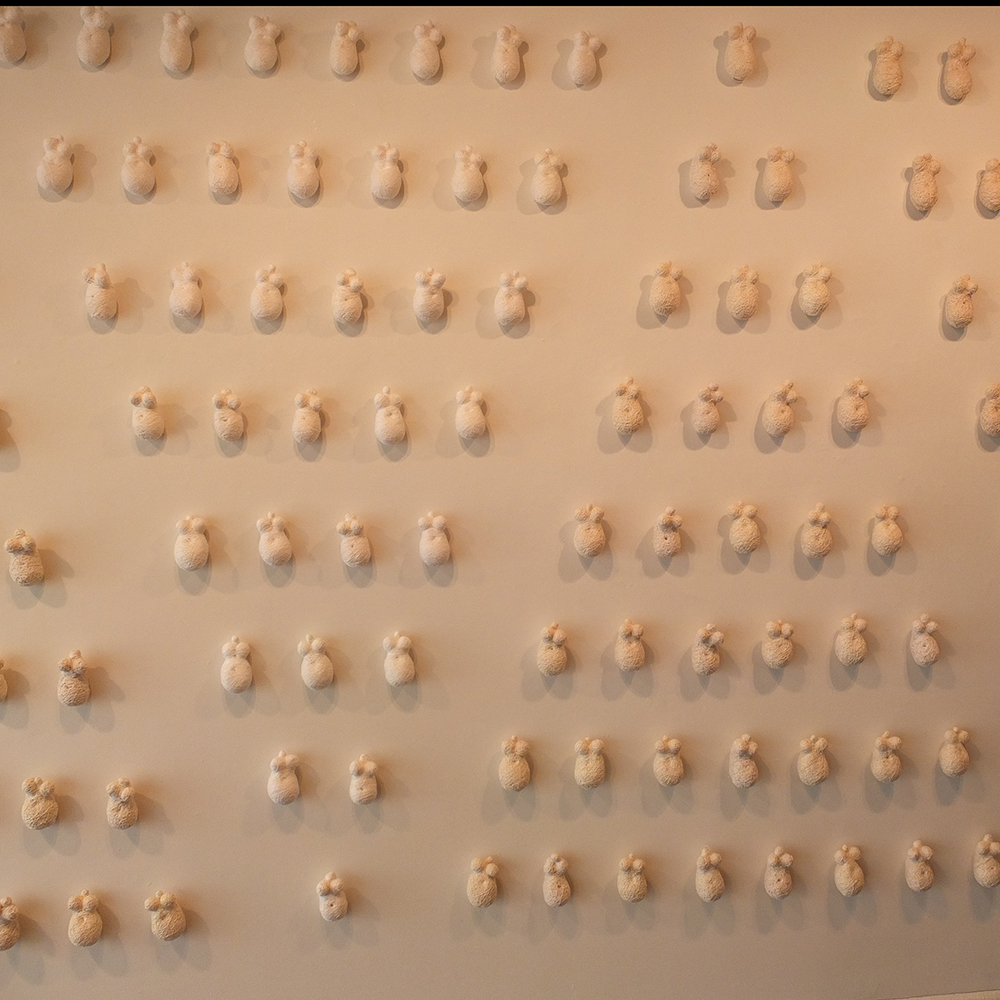

While I was becoming an American, I also became a mother. It demarcated my life into two stages: having a mother tongue (29 years) and having motherhood (25 years). Balancing a career and a family is the story of many American women’s lives. It is a struggle that comes with acutely painful choices. Being a mother was in many ways a burden to my career, but it was not without its joys. It enriched my life with love that I would not have otherwise experienced.

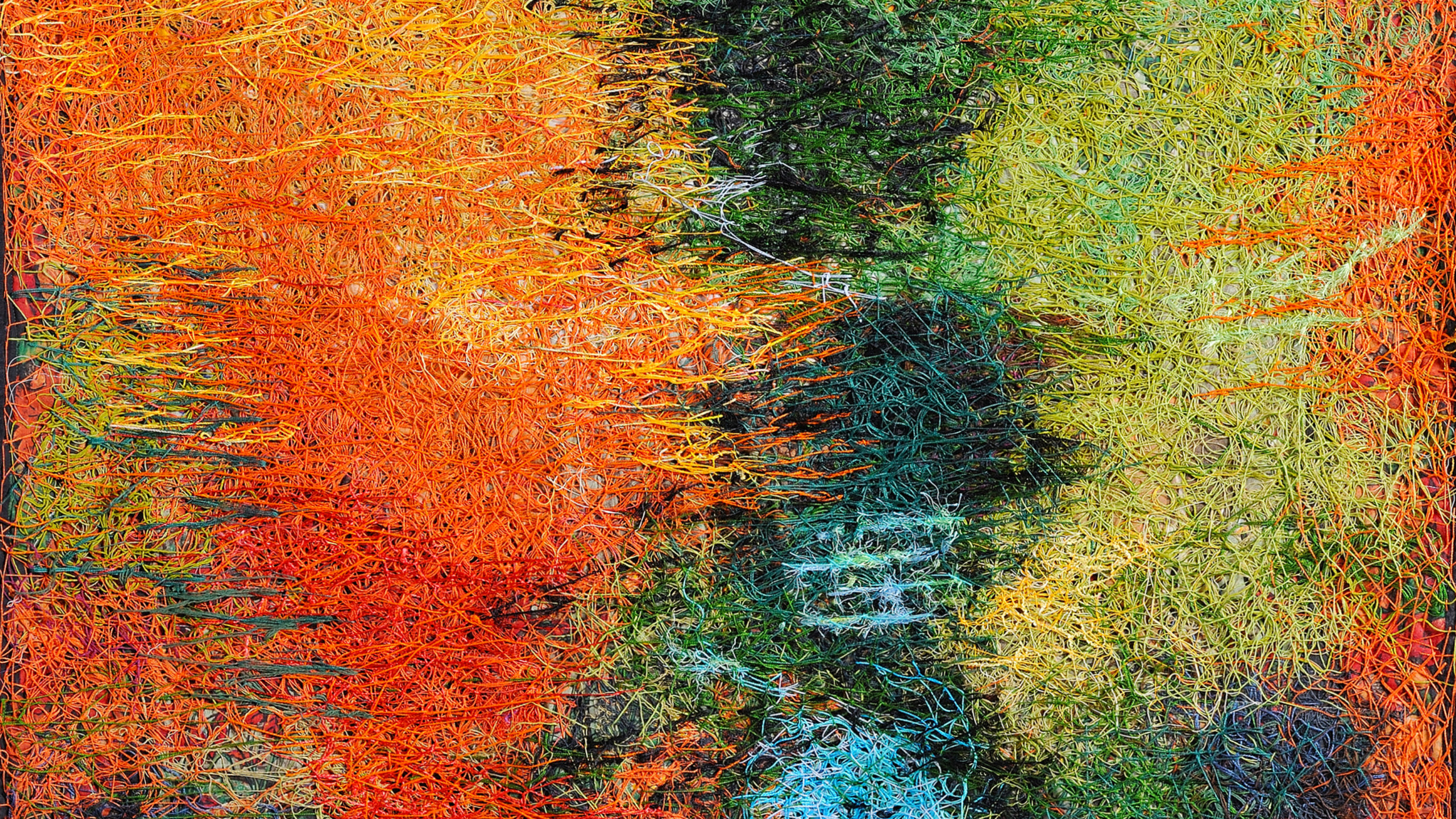

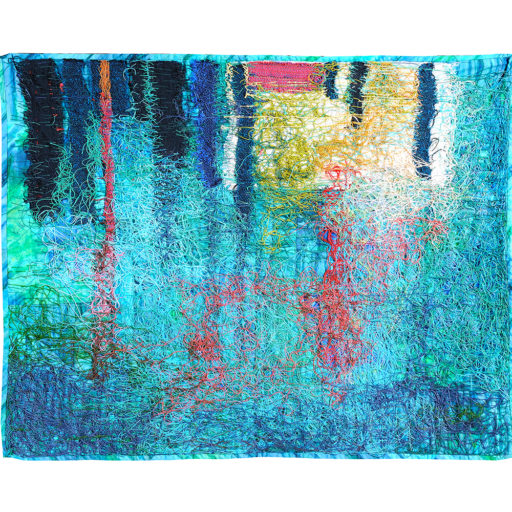

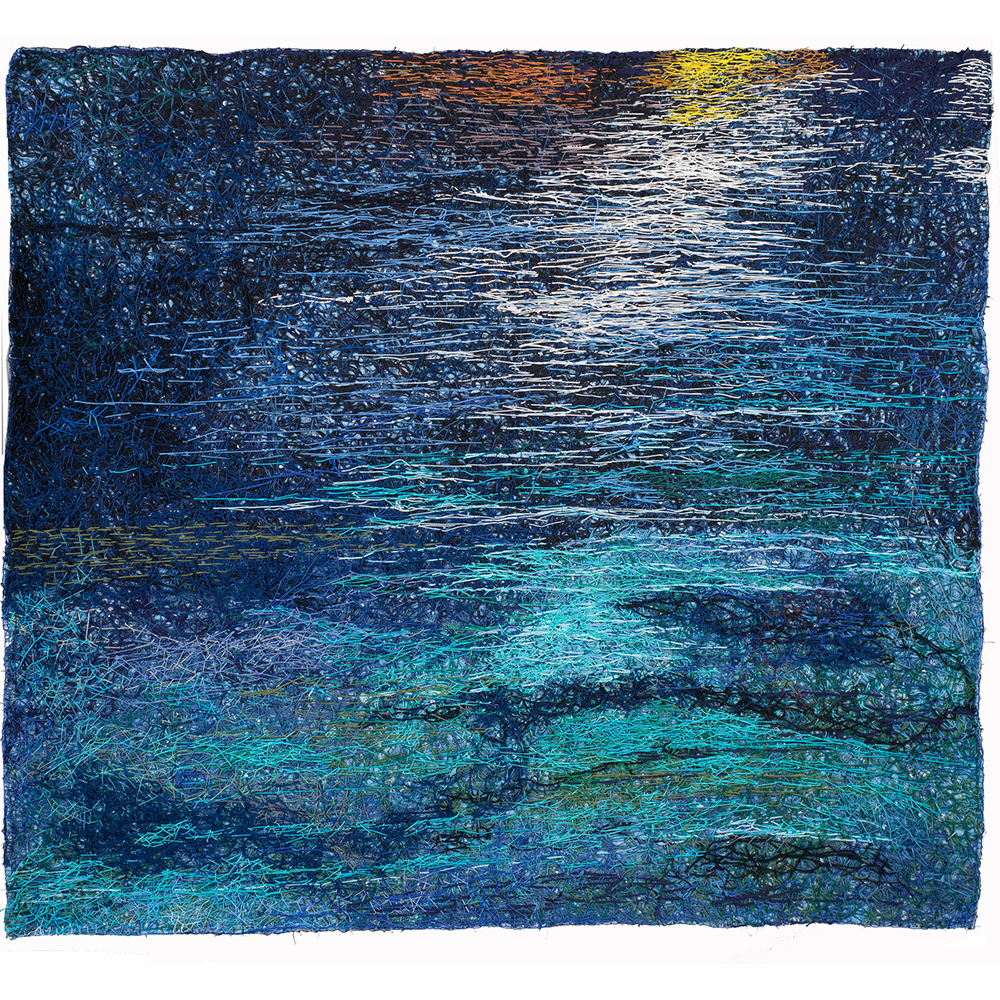

These two events happened largely at the same time in my life, and I began to see links between the two. In birth, a person must let go of their mother, cease to be connected to her body. In the same way, I found myself having to let go of my mother tongue in order to have a voice in this new place. In these frustrations I found incentive to find yet another voice in my artwork. In the visual, I found more freedom and refuge from the struggles that accompany language barriers. It’s these tensions that I seek to explore in this body of work. Is motherhood a shackle or a wing? Is a mother tongue a yoke or an anchor?